Sgt Tom Nowell MM – Korea

Tom Nowell was born in Goldthorpe, South Yorkshire on the 23rd of November 1922. He comes from a family of eight children, four boys and four girls, his father was a Mine’s Inspector. Tom attended school in the Dearne Valley, As there were few jobs available he followed his fathers footsteps and became a miner.

At the outbreak of the Second World War, mining was designated as a reserved occupation, so he could not enlist into the regulars. He volunteered to serve in the Home Guard, obtaining the rank of Sgt and eventually the rank of Lieutenant. In 1948, when the ‘reserved occupation’ regulations were lifted, Tom enlisted into the Regulars and was recruited into the York and Lancaster Regt, his parent Regiment. Wartime Homeguard ranks were not retainable for Regular service, this required Tom to start again as a private. During training it was discovered he could shoot well, and he remained at the depot as a weapons training instructor, again rising to the rank of sergeant. When the Korean War started the Dukes had been reduced to a strength of 600 men, as time expired personnel were discharged from the army. Tom was rebadged as a Duke and served with the Dukes throughout the Korean War as a Sniper Sgt and Intelligence gatherer, from his excursions beyond the front lines. What follows is an excerpt drawn from Tom’s memoirs, an audio recording of which is held in the Regimental Archives:

“The advance party for Korea was to go to Pontefract, in Yorkshire, England, to form up and be made ready. I was put on this advance party and assumed my service role of Sniper and Intelligence, this was the role I was to oversee when the Battalion arrived in Korea.”

“We arrived in Pontefract, and after a couple of days getting sorted out, we were given a few days leave and told to report back.”

“We were then transported down to Southampton and put aboard the Troopship HMT Empire Orwell, quite a large ship, as they went in those days. On this ship were other units who were on a similar errand, ‘all going to the Far East’.”

“This was the back end of July 1952 and British troops were already out in Korea, being drawn from the Far East Stations of Hong Kong and Singapore. These were the nearest troops we had out there at that time. We were to get out there in time to relieve them and allow them a well earned respite from the rigours and privations of the Korean climate and hostilities… the Korean winters could be quite fearsome, we were told.”

“During the sea voyage we did some training and listened to some lectures on the peninsula of Korea and the pitfalls that we may have to overcome, including the health side of it. Travelling in the Mediterranean was pleasant enough. At the island of Malta we pulled into Valletta Harbour, this was only a brief stay and we did not get the chance to go ashore. The Orwell then set course for Port Said in Egypt, at the Northerly end of the Suez Canal. When we arrived there, we had to await clearance to go down the Canal.”

“It is an eerie sensation going down the Suez Canal on as large a ship as the Orwell was. One wondered how they managed to get enough sea water into the canal to keep these big ships afloat and moving. We were required to go down slowly so as not to make too much ‘wash’. We were heading for Aden at the lower end of the Red Sea, just before the waters give way to the Indian Ocean.”

“The temperatures in this part of the world were high and uncomfortable. After a brief stop in Aden we set sail out into the Indian Ocean, heading for Colombo in Ceylon. The weather was hot and sticky, even though we were out at sea.”

“After Colombo, the Orwell set sail for Singapore, going by way of the Straits of Malacca and down the coastline of Malaya. The passage through was a bit rough, the troopship being thrown about a bit in the process. However the weather cleared somewhat, and we settled down to something like normal before we got to Singapore at the end of the Peninsula. At Singapore there was the briefest of stays, no shore leave, and the Orwell set off for the journey across the China Sea, towards Hong Kong. The seas were pretty rough.”

“At Hong Kong we were astounded by all the activity that was going on in the harbour and on the waterfront. Our troopship had quite a lot of stores and linen to change so we were offered shore leave. Eventually we put back out to sea, heading for the port of Pusan in the southern part of the Korean Peninsula. This was the largest port available to the United Nations Forces at this time.”

“At Hong Kong we were astounded by all the activity that was going on in the harbour and on the waterfront. Our troopship had quite a lot of stores and linen to change so we were offered shore leave. Eventually we put back out to sea, heading for the port of Pusan in the southern part of the Korean Peninsula. This was the largest port available to the United Nations Forces at this time.”

“As the Orwell threaded its way north, through the group of islands that were dotted about the Southern coast of Korea, and headed into Pusan proper there was an unmistakable stench of fertiliser. It permeated all over the place, the smell was to be found all over the Korean Peninsula. The big ship nosed its way into Pusan Harbour, and proceeded to tie up. We had arrived in Korea!”

“There were formalities to be observed, such as the greetings from the local dignitaries of Pusan, a group of little Korean children garlanded our ship’s CO, Major Charles Grieves, with flowers much to the cheers from troops aboard the ship. There was an American forces band on the quayside, who played for us in greeting… it was most enjoyable but left a mixed feeling in the mind as to just what we were in for.”

“Once the off-loading of men and supplies had been completed, we were given some haversack rations and put aboard a train that was to take us northwards to the area of the front.”

“It was to prove to be a long, tiring journey and most uncomfortable journey, travelling through the night without stopping. The next day, near lunchtime, we arrived at the detraining point known as Tockchon. We alighted and were bussed up to a reserve area just behind, what was then, the front line. We had arrived! The next thing to do was to get organised and into some sort of order. We were to travel up to the front line proper the next day, to join the Regiment that was to be our base until our own Regiment came into the country as the main party.”

“The noticeable thing about Korea was one of hills, not really big mountains, but high enough hills nevertheless, as fast as you got by, or over, the one in front then there was another one to go up or down. The lower parts of the hillsides were terraced and made into paddy fields, making the most of what ground there was for the cultivation of crops. The remains of the terraced bunds, or banks, were still visible, even though the war had ravaged them as a result of the shelling and constant bombardment and diggings.”

“We joined the Regiment in the line . . .this was to be a time of learning – the position of supplies, positions of your own and enemy displacements etc, where and to what extent did our patrols operate? What type of patrols were needed, and at what strength? Having to go out at night with your opposite number on patrols and observing what the other patrols were doing or achieving.”

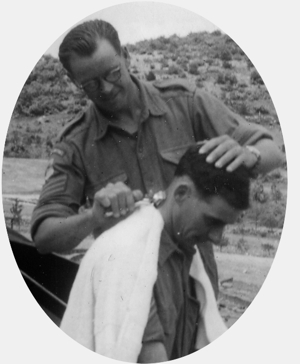

Tommy Nowell also tried his hand at barbering by cutting the hair of Sgt Bill Norman, from the Battalion Mortar Platoon, for a fund raising Appeal. Which Bill did not let turn into a regular event.

Tommy Nowell also tried his hand at barbering by cutting the hair of Sgt Bill Norman, from the Battalion Mortar Platoon, for a fund raising Appeal. Which Bill did not let turn into a regular event.

“The Regiment that we, the Dukes, were with, was the Welch Regiment. They were a fine crowd and easy to get on with. We settled in well to their routine, it was important that we learnt the business fast so that when our Regiment came into the conflict, there would not be any break in the continuity of actions.”

“Patrolling at night certainly sharpened your reflexes and senses. The sound of your own breathing sounded like a hoarse rasping, although it wasn’t really, you were aware of your pulse throbbing to the point that you were sure people around could hear it loud and clear. A period of mental training and preparation was required to be a success at night-time patrolling and reporting – you could say that self discipline was a must.”

“The portion of the front that we were allocated responsibility for at that time was considered a quiet sector, but as things turned out it could change quite easily into a hotbed of activity. A sudden flurry, or burst of action, caused the front to erupt into a hot and fearsome shooting war with both sides going at it ‘hammer and tongs’. It was all a question of who held the highest hill around, and how he dominated the surrounding area. If the enemy thought that the hill you were on was a threat to them and of benefit to you, plans were put into operation to take that hill from you and deprive you of the use of it, thereby putting you and yours in danger. Vigilance and watchfulness was the order of the day.”

“Soon, the time came for the Welch Regiment to go out of the line and into reserve, to make the change-over with the new Regiment, the ‘Dukes’. They would then be free to ease out of the conflict and prepare for posting home.”

“Most of the winter months were spent in a sector called Nai Chon, and the ‘Dukes’ did a lot of good work here. Patrol activity increased and there was always something to be fighting about. The enemy was intent on pushing as far as they could get so they would be in a strong position for any armistice or settlement talks.”

“From early November to late March, in Korea, winter sets in and the freezing cold winds from the North East, mainly Siberian, were sufficient to keep the temperatures down into the freeze zone and the ground became frozen to a depth of some feet. Excavating the ground in order to make a safe ‘hoochie’ could only be achieved by blasting the ground with explosives – picks and shovels were not up to the task on their own.”

“New types of wet winter clothing were getting through to the British Forces and although it emanated from stock that was devised and kept for the Norwegian Expeditionary Force, two world wars ago, it proved to be good and warm. There was an inner and outer parka with a hood and toggle arrangement that pulled the garments together to keep out the cold winds. Heavy woollen socks and nylon inserts for the cold, wet weather boots were also issued. To top up the protection we had ‘Long Johns’ and string vests which proved to be very effective. Inner and outer gloves also made for good protection, but in the moments of leaving your hands free for chores, such as loading your weapon, you stood the risk of your hands becoming stuck to your rifle.”

“New types of wet winter clothing were getting through to the British Forces and although it emanated from stock that was devised and kept for the Norwegian Expeditionary Force, two world wars ago, it proved to be good and warm. There was an inner and outer parka with a hood and toggle arrangement that pulled the garments together to keep out the cold winds. Heavy woollen socks and nylon inserts for the cold, wet weather boots were also issued. To top up the protection we had ‘Long Johns’ and string vests which proved to be very effective. Inner and outer gloves also made for good protection, but in the moments of leaving your hands free for chores, such as loading your weapon, you stood the risk of your hands becoming stuck to your rifle.”

“When ensconced in your hoochie, heat was produced by a petrol or diesel ‘chuffer’. This was made from an empty ammo box with a little sand, or soil, in the bottom with a series of holes around the base. A petrol pipe tube from outside the hoochie was the power source and some sort of nipping to the pipe or a valve would control this flow of fuel. A length of stove piping took the soot and fumes out of doors, and you were in business. That is, until the pipe got clogged up with soot or was hit by a stray piece of shrapnel, then it was a case of sooty faces and a dash to the entrance to get some air and to effect a repair to the central heating. In the first months of the Regiment’s stay in Korea, it was estimated that we had more casualties from the effects of these stoves back-firing than from enemy action.”

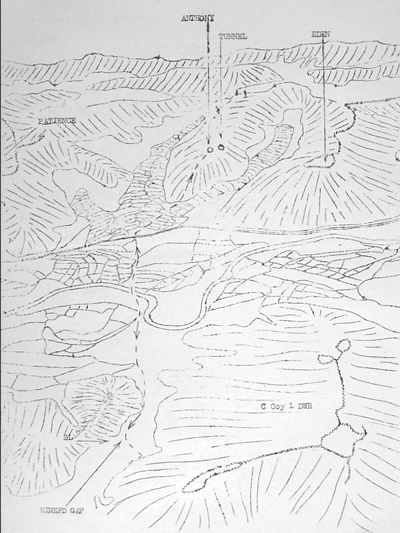

“We had an idea about the patterns of activity on the features known as Winston, Churchill, Antony, Eden, Wellington and Boot. These were the code names that we used to describe the various features opposite us. A few weeks before Christmas 1952, we saw what we thought at first to be some repairs being carried out on the feature Eden. There were two men working together and by the look of their clothing they were either living or working in a dusty place. It soon became obvious that these two were working in the side of the hill, and the movement that we saw was when they were coming out of the entrance of their tunnel and emptying a make-shift barrow of earth and spoil down the hillside facing away from us. My position gave me a good view of where they were and what they were up to. We observed them for the rest of the day, and then at nightfall we made our way back and made our report to the Intelligence Officer. We were given orders to concentrate on this particular feature and keep tabs on what progress these two workers were making.”

“One morning we saw a person appear who was cleaner in appearance and wearing a fairly clean uniform. He was talking to these two Chinese workers, now known to us as Little Dusty and Big Dusty, and it looked as if he was giving them a right old ear-bashing. He was their Commissar and he was giving them their weekly pep talk and urging them on to better output.”

“The observation of these two was now well advanced and the report led the CO to realise that a more detailed look was required. It was decided that a young officer, Ian Orr and myself would go out on our own to have a look around and try to find out a little more about the tunnel and its environs. This particular patrol was to become a most gruelling stint and entailed going over and staying out there the whole of that next day, making our way back at the end of the next night. The temperatures at this time of year had been recorded as the coldest of the winter so far.”

“I went down to the company dug-out and joined up with Ian Orr. After a conference with the CO and a final briefing, we were escorted down to the wire and minefield gap. There we were bid ‘a good patrol’, and ‘the best of luck’, and we were off.”

“I went down to the company dug-out and joined up with Ian Orr. After a conference with the CO and a final briefing, we were escorted down to the wire and minefield gap. There we were bid ‘a good patrol’, and ‘the best of luck’, and we were off.”

“Threading our way down the remainder of the hillside and negotiating the minefield and extents of the wire, we made it to the first bund, the objective we had set ourselves. The night was fairly dark, the moon had not broken through the clouds and we wanted as much darkness as we could get. What a noise we seemed to be making. The ice underfoot crackling and the sound of foliage swishing through as we tried to step carefully. As we went along picking out our landmarks and our ‘leaps and bounds’ we kept talking down to a minimum and made do with the odd sign, or grabbing one another’s arm for attention. We both felt naked out there but, having got past the point of no return, we concluded that it was now safer to go forward than to retrace and go back.”

“Suddenly a series of clicks and bangs went off and the sky was illuminated by a string of flares and tracer that lit up the sky, there was obviously some disturbance further down the valley and for a short time there was quite a racket going on. We were travelling light, a couple of hand grenades, a Sten Gun and no radio cover. We were to make notes, or mentally take stock of the layout and fortifications that were there.”

“We came to the foot of our objective and decided to go around and further into the enemy territory to come up on the hill from the rear. Climbing up the slopes we made our way along the ridge of the outcropping feature and came across some large logs that were being used for the construction of the tunnel, so we knew we were on the right track for the tunnel itself. Getting near to where we thought the tunnel entrance should be, we split up and were to make separate hides, or observation points, that were to be our position for the rest of the next day. Ian Orr stayed at that point and I decided to go further forwards, where I thought the tunnel entrance should be. Out with the jack-knife then, I cut some small firs that were growing in the area and fashioned them into a sort of cover.”

“Having made everything as ready as I could, it was a case of settling myself in and making myself as comfortable as I could. I had a self-heating can of soup in my supplies and activated the striker. God, what a noise! The crack that it made sounded like a gunshot going off and as it warmed up, there was the inevitable sizzle sounding like a kettle about to blow its whistle. I couldn’t stop the thing and it seemed to be getting louder. I tried to smother it against my chest to quieten it, only to be showered with hot, steamy beef stew!”

“When daylight finally came, I found myself in my little hide just on the lip of the entrance to the tunnel. I had a grandstand view of what they were up to all right, but I was too close for comfort. With this and the bitter cold I was in a most precarious position.”

“Little Dusty came away from the mouth of the tunnel and made to come in my direction, ostensibly for another tree log or something. It turned out that he wanted a pee, so I had the indignity of having my homemade hide pee’d on by a Chinese labourer. Apart from that, he splashed me in the process but the wonder of it all is that he didn’t see me in the hide.”

“All the time we continued to note as much as we could of the enemy tunnel and the size of the logs etc, it appeared that they had almost finished construction.”

“Although the gunners and our mortars had been given the order not to fire on this particular feature during our mission, there were a couple of occasions when they did open up and one bombardment came uncomfortably close, a sliver of one of the shells cut a furrow up to where I was laying. It stopped just short of doing me an actual injury.”

“The enemy night shift returned to take up their positions again. As far as I could make out there were seven or eight in the new patrol. They came over and settled in a group on my side of the tunnel entrance. My limbs had been stuck all day in one position without being able to stretch and relax, but after what seemed like an eternity I managed to get far enough away to ease my stiff limbs and work my way back to where I last saw Ian Orr. I explained to him what was going on and that the enemy were situated in front of us. We decided to go further, deeper into enemy country, and circle around the enemy patrols. My outer garments by this time were frozen up and it took quite a while to get the circulation back to my feet. When I got some feeling into my limbs we set off. I have never been as cold in all my life, the thought of being able to do something to ease the pain of the cold now was a blessed relief to me.”

“We set off on our return journey and proceeded to go around and to the rear of this position. With a lot of care where we trod, and how fast we moved, this route helped us to pass the enemy patrols and make it down off the hill and out into no-mans land. There was still the valley to travail and we had no idea of the patrol plans of both sides involved, so it was a case of playing it by ear. What had appeared a straightforward return proved complicated on the inward run. We stumbled, rather than stepped, and our reference points seemed indistinct and confusing. We approached with as much caution as we could muster when we were challenged by a patrol of ours. Not knowing the changed password there was some moments of confusion as to who we were until someone piped up that we must be the two who were expected in sometime in the morning, and they were to keep an eye out for and render assistance if needed. We were escorted through the minefield and wire to the approaches of the Company HQ, where there was a welcome meal being prepared. Whilst we were having this meal we were able to give the Company Commander as much of the information as we could that affected his part of the front.”

“I was given transport back to my hoochie at Battalion Headquarters, which I shared with the Intelligence Sergeant, Tony Goddard. He helped me out of my still frozen clothes and gave me a good rub down with a warm blanket and then I was put to bed.”

“The debriefing was intense and because of the proximity of the Chinese workers and the freezing cold, I had only made notes of the important points of the stay-over. I had committed all else to memory, so early de-briefing was essential. All in all it was considered a successful patrol and a decision was made to send a fact finding patrol of some strength to find out the inner size and strength of that tunnel. Now, who were the two most likely people to lead this patrol? Obviously the two who had been over there and had already ‘sussed’ it out, namely Ian Orr and myself.”

“The planning went ahead and the time came when the CO decided that conditions were favourable for this to go on. Everything that could be done to ensure success was done. It was to a night patrol and all back-ups were alerted.”

“Good progress was made at the outset, but things got a bit hairy when approaching the foot of the enemy hill position. There was activity afoot, and the diversions that we had organised did not seem to be having any effect. The possibility of further work having been done to the warning system of the new tunnel could not be overlooked. We had decided to make an approach from the front and make a sudden storm of the tunnel entrance, hoping to catch the enemy napping and to take some prisoners.”

“In the event, the Chinese had been disturbed by the diversionary tactics that had been set up and were fleeing the tunnel when we got there. I was in charge of the fighting side of the party and we followed the enemy further into their territory, leaving the tunnel party to get into the tunnel and make their observations. We pursued the enemy to the top of an outcropping spur, and I considered that to continue any further would separate the two parties needlessly so I called a halt. A thorough inspection of the tunnel and its workings was made, to ascertain how many troops or guns could be housed there. There were signs that the Chinese were grouping for a fight.”

“Seeing that we were in their territory and could get off the hill, away from the relative safety of no-man’s land, it was decided to re-group and head for our lines again. The tunnel party to go out first and the fighting party to cover the rear. Up to this point we had fired no shots but now there was every likelihood of a shooting match and there was considerable tension. The darkness of the night led to some confusion. Flares were being sent up and if the enemy did not know where we were before, they did then. All hell broke loose and for a while it looked like we were going to have some casualties. Making our way through no-mans land was quite a noisy affair with constant stoppages for listening and observing. The light was beginning to break and we were aware we had overstayed our time there. We were thankful to reach the safety of our own wire and minefield approaches to the Company area, from where we had originally set out. There the QM had laid on some hot drinks.”

“It was then decided that a party would be led to destroy the tunnel.”

“I then got a set-back. I was informed that I wasn’t ‘to be going on this one’ and that I was ‘to help with the administration instead.’ I couldn’t understand it. I thought they would need my experience of the hill, but they had decided that I had done more than my share of dealing with this troublesome feature and that I was to rest this one out.”

“I had mixed feelings; because I had fully expected to be going, firstly I had feelings of being let down and angry; then the other feeling of relief of being spared the ordeal of what it entailed. Everyone round about thought I was mad to be even wanting to get involved in this raid, and some wag had scrawled on my hoochie front porch – ‘Nutter Nowell Lives Here’.”

During a daylight raid the demolition of the tunnel proved a success. Tom was subsequently awarded the Military Medal for his role in the gathering of vital information during his 36 hour hide-out. The April edition of the Iron Duke, 1954, Page 69, Records a MM being awarded to Tom Nowell and Cpl MA McKenzie, plus a further MiD for Distinguished Conduct in Korea to Tom Nowell.

This is a partial record of Tom Nowell MM’s Service in the Duke of Wellington’s Regiment, during the Korean War (1952 – 1953).

Interviewed by Tracy Craggs, Regimental Archives Dept, Audio Archivist.