Cpl Peter Walker – WW2

The war started for me when John Marsland, who worked at the same mill as me, and I, decided to join the Territorial Army, rather than wait until the balloon went up and probably lose all chances of making up our own minds as to where and in what we served. So, one May evening in 1939, John and I turned up at an empty shop in Cow Green, Halifax and then, having coughed for the M.O., who then listened to our hearts, we were signed on as members of the 2/7th Battalion the Duke of Wellington’s Regiment. Training started in the R.E.S. gym in Great Albion Street. There, every Tuesday and Thursday night we spent two hours from 7 until 9 o’clock doing very elementary military training – foot drill – rifle drill – learning parts of the rifle and aiming and squeezing the trigger of the same – stripping and reassembling the Bren Gun.

Peter was given the current basic day’s pay each time he had accrued eight hours. He was soon promoted to Corporal. In August he first experienced firing live ammunition during a training weekend, at a firing range, he was also given some webbing equipment to take home.

This was our first bit of uniform and was out of date First World War stuff. On Friday September 1st, John rang me up at work, just after dinner. He told me to report to the R.E.S. gym straight away, with my webbing equipment and washing tackle. It was a very scary yet exciting bus ride into town – the afternoon was hot and the bus windows were open as were the doors of the houses on the road side. From these doors came the sound of wirelesses turned up loud and the sound of announcers calling out the orders to the reservist, Army, Navy and Air Force, telling them to which Depots they had to report. It filled me with excitement; tinged with apprehension and, I suppose, fear.

On arrival at the gym we were issued with our very own rifles and bayonets and told to wait until the Company was complete, when we would be getting our orders. Fortunately we were issued with a mug of hot sweet tea and a bully beef sandwich, as it was dusk before orders finally came – not that it made any difference to the rank and file – confusion seemed to reign supreme.

Peter’s platoon was taken by bus to Walsden and the end of the Summit Tunnel. The Company was to defend the tunnel from saboteurs – both German and IRA. They returned to Halifax a month later, now kitted out with battle dress.

On our return to Halifax we were billeted in Maudes Temperance Hotel. There our training consisted of marching round Halifax, doing footdrill and bayonet drill both with and without gas masks.

In December, the Company was detailed to guard Standege Tunnel, on the Huddersfield – Manchester railway line.

Soon after Christmas I was recommended for O.C.T.U and transferred to ‘W’ Coy in Huddersfield where all the potential officers were concentrated. By now we were fully equipped with up-to-date uniforms and webbing equipment, if not with weapons.

In March 1940, the Battalion prepared for pioneering duties in France. After a church parade at Huddersfield Parish Church on the 28th of April, they left by train for Southampton and boarded an Isle of Man passenger ferry. The next morning they arrived in Cherbourg and after some delay, a train consisting of cattle trucks and a carriage for the officers, took them to Blain, a small market town about 20 miles from Nantes in the Loire Valley. W Coy was to act as loaders for the RASC, moving petrol, oil and lubricants from trains arriving from Nantes to awaiting RASC trucks.

By May the 17th things were not going very well for the Allies and our three, less than half trained, half armed divisions had been changed from Lines of Communication troops to front line divisions.

Eight o’clock on the evening of the 18th of May saw the Battalion marching down to the station, headed by the band and drums who were going with us, just as in the days of Marlborough or Wellington. For food we had one day’s rations.

The battalion travelled to Rouen and met up with the rest of 137 Brigade and another Battalion, the 2/4th KOYLIs from 138 Brigade. They were bound for Bethune via Amiens but the railway bridge over the Somme had been destroyed by the enemy so they were diverted through Dieppe to Abbeville. On approaching their destination they came under attack from German bombers.

In the near distance, from our train, the bombing and fires in Abbeville could plainly be seen and it became obvious that the Germans had occupied the town. The only way we could now go was backwards towards Dieppe. The KOYLIs made their way back on foot, mainly owing to lack of transport. The trains carrying the two ‘Dukes’ battalions had come to a halt on an embankment and could not be unloaded without being moved back to more level land. To make matters worse, night had fallen and it had become dark. After travelling back about five very long, jerky miles we came upon another bombed section of the line and were forced to halt.

Having unloaded two utility trucks, one was taken to make contact with other units and the other was taken by a party led by Lieutenant Smith of the 2/7th DWR for a reconnaissance. This truck came under fire from the Germans near Abbeville and Lt Smith was killed by a machine gun bullet and the rest of the party fled. The remaining men of the two battalions took defensive positions on either side of the train.

The defensive position took the form of a line of soldiers lying on the ground armed with a rifle and 50 rounds of small arms ammunition per man, with a Bren gun, with only one magazine, per platoon. We were lying flat on the ground, because we had neither pick, shovel nor entrenching tool. During the day there was much enemy air activity, although luckily not near our position, and through some good chance we seemed to have been missed by the spotter planes. Scouting parties had been out all that day searching for the last line of retreat and had found that the railway lines to the rear had been blocked for about five miles, by bombed trains and tracks. It was decided to march back to find a better defensive position and see what turned up.

As we started the march back in the direction of Eu, in the vicinity of Fressenville, we came across several trains that had been bombed. Some were civilian trains and had obviously been evacuated in a hurry, except for those unfortunates who had been killed. The sight of two carriages wedged up in the air, with a woman hanging upside down from the buffers, is something that will remain with me forever. Unfortunately, being without tools of any sort we were unable to bury the dead until later.

We were, however, able to free some horses from what was evidently a train transporting either French or Belgian cavalry… A dog which we freed from the train quickly became attached to the battalion and they say it remained with us to the end. The last train we passed was a hospital train containing French wounded. The CO promised to get help through to the hospital and the battalion took up a defensive position in a wood near the railway line.

The battalion had very little food and water and sent a scouting party to find supplies. They found water at Chepy-les-Valenes railway station. They returned with a request to provide protection and to help repair a train that had broken down, enabling the hospital train to continue. The 2/6th Battalion left for Rouen on foot leaving the 2/7th assisting at the station. They soon received orders to make their way to Dieppe and form a defensive line along the river Bethune, inland. They also received news that the hospital at St Valery-sur-Somme had been evacuated. A truck was sent to collect any remaining food to sustain the men before they were loaded into cattle trucks bound for Dieppe. The journey took several days and on arrival they were accommodated in an empty POW cage. They stayed for a few days during which one of the battalion signallers read a message from a Naval vessel to the Dieppe Harbour-Master, – the evacuation of Dunkirk was being completed.

During our stay in the POW cage we had a grandstand view of the first bombing raids on the port. Previously it had been spared bombing as a hospital port but the movement of troop trains through the port and our subsequent arrival had been noticed by the enemy and on the first bombing raid five ships, including a hospital ship, were sunk.

‘W’ Coy moved to the race course and dug weapons pits but were soon withdrawn after a bomber attack and were billeted in a house. They established a road block on a minor coastal road. Scout parties brought food and looted equipment.

I am still left with the memories of the seemingly endless columns of refugees with their cars and carts piled high with household possessions and those without transport trudging along with their pathetic little bundles in their hands and on their backs, the fine weather, the way in which one’s spirits sank in the loneliness of the 3am to 4am morning guard duty and tins of petit pois, the only things we were able to buy from the one remaining shop that was open.

On the 7th of June, Peter’s platoon was moved to the west bank of the River Bethune. Three days later, the bridge over the Bethune in Dieppe was destroyed and they prepared for hostile attack.

“Our hearts seemed to drop with a feeling of ‘this is it’”.

At about midnight, the battalion marched to Petit Appeville where transport was waiting to take them to Veules-les-Roses, a small port. They took up defensive positions and awaited Naval evacuation back to England. As dusk fell, a number of tanks approached.

There would be about 40 or 50 tanks attacking across our frontage, firing into the wood with their canon and machine-guns. Fortunately the ground sloped fairly sharply down from the attacking tanks to the road behind our wood so they tended to shoot high. As a result, in our area of the combat, there were comparatively few casualties from machine-gun fire or direct hits from the tank canon. The greatest number of wounds were due to shrapnel from the canon shells as they burst among the trees and minor wounds when the bursting shell blew chips off the trees with enough force to penetrate the skin.

As the attack continued, from out of range of our weapons, a few of us took shelter in a slit trench that somebody had been able to dig. Soon darkness hid us all and having had no orders to retire we stayed where we were. Under the influence of three or four days without sleep, we nodded off and woke up at intervals through the short night.

When we all came to at sunrise we could hear the sound of Germans searching the wood and the rattle and roar of armoured vehicles and motorbikes on the outskirts of the wood. After a short discussion our little group came to the conclusion that any heroics would be useless so we came out of the wood and surrendered to the Germans. Amongst those taken prisoner with me were:- Captain T. Warton ‘Y’ Coy, PSM Douggie Harper ‘W’ Coy and CQMS John Marsland.

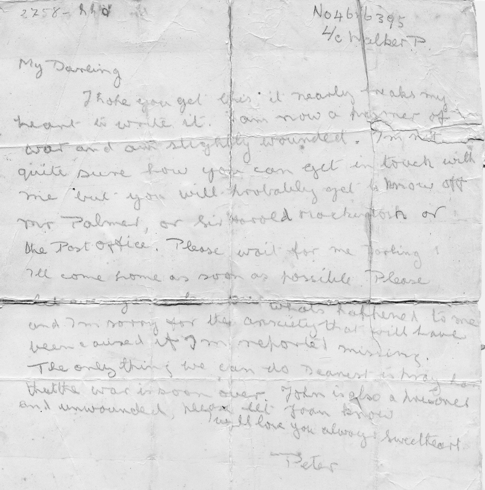

Peter had a shrapnel wound on his shoulder, although his webbing straps had given him some protection. He was taken to a field dressing station in a casino at Forges-les-Eaux and treated by a German medical orderly who gave him an anti-tetanus injection. He spent the next two weeks recovering there.

The time was spent in waiting for the next meal – one bowl of thin soup and one thin slice of French bread twice a day – and as soon as it became possible, wandering about the casino grounds looking for anything useful, edible, or upon which we could write home.

Peter did manage to write and sent three letters to his family, which took two months to arrive home. This was the first news they received and they informed the War Office of his situation. When he had recovered he was marched. with three other British and sixteen French soldiers, to dismantle some Nissen huts and marquees which had been part of British No.1 Base Depot. This was known as ‘Organisation Todt’.

The staff of No.1 Base Depot must have left in somewhat of a hurry! When we came to clean the kitchen and dining area we found ourselves dealing with breakfast plates with the half-eaten bacon and egg breakfast still on them. In the dining tent were soyer stoves half full with maggot ridden, half-cooked stew, several weeks old. We cleaned up all the plates, Soyer stoves and utensils for the Germans, also the toilet buckets out of the latrines. Our most unpleasant job was burying a month, to six week, old corpse of a horse. For the latter we were given British gas masks and a bottle of brandy, we provided ourselves with anti-gas gloves which were lying about in profusion.

‘Otto’, our guard, had an evil, unshaven, piratical look about him, he came from East Prussia where he said he had a reputation for horse smuggling. He was actually quite reasonable and gave us no trouble.

The prisoners were permitted to take any clothes left in the depot where they also found plenty of paperback books. They continued to clear the camp until mid December when they were moved to St Laurent-Blangy, a small village on the outskirts of Arras, and continued labouring.

At Christmas we each received a Xmas box consisting of a small, rather hard, piece of spice cake and a few cigarettes from O.T. along with the Germans. We did not however feel very much in the festive spirit. We just thought of all those at home and missed them. For all of us it was our first Christmas away from home. We were all very homesick and without any real news of what was happening at home.

After Christmas, Peter remained with Operation Todt with another British and four French prisoners. The rest were sent to a camp in Germany.

Jock and I did general odd jobs around the chateau and anything that tickled Otto’s fancy. Amongst the fads that took his fancy was fishing, as he said they did it even in the midst of the East Prussian winter… it was as we were passing our time with these fishing expeditions that we first met two French ladies and a seventeen year old girl.

Mme Evans, Mme Devienne and Elizabeth, the French ladies, visited Peter and Jock, first bringing them cigarettes and biscuits, then asking them if they would like to escape as they could provide help and shelter. The men decided to make an attempt and planned how to get out of the building.

We decided to take a couple of sandbags up to our room after work on the day of the escape to provide a hessian wrapping for our boots. We hoped this would quieten our footsteps… we hoped to creep silently from our room, down the top flight of stairs, through the window already opened, creep along the balcony to the end opposite the stairs and climb down the drain pipe.

On the evening of the day of the escape everything went very well, we managed to get the sandbags and sneak the window open, without being noticed, on the way up to our room. The minutes seemed to pass like hours as we waited for the time to escape and in the end the waiting proved too much for Jock, he cried off at the last moment, wished me good luck and told me to go it alone. As half past eight approached I went.

Peter managed to climb out of the window and down the drain pipe. He waited in the bushes for his friends to arrive. He was taken to Mme Evans’ haberdashery shop and given a meal of fried eggs and chips.

“I was wet through and trembling from tension – after all it was not something that one did every day.”

He spent two weeks hiding in the shop and the villagers treated him very well. He began to dress as a civilian and was given a French name – ‘Henri Beaujean’. Soon arrangements were made to pass him further down the escape line and he was smuggled into the back of a truck bound for Lens.

|

|

|

Peter on his French identity card as Henri Beaujean |

Mme Evans and her friends continued to help British soldiers escape until May 1941 when they were betrayed to the Gestapo, kept in solitary confinement for nine months, and then deported to slave labour camps in Germany, although all three survived the war.

In Lens, Peter was hidden with two British soldiers and they were given identity cards. They soon left with six young Frenchmen hoping to join the Free French in England, or to get into the unoccupied zone. They made for Paris in an old carriage next to the engine of a coal train. Some German soldiers boarded, unaware of the prisoners in the old carriage and this helped, as the staff at the control station chose not to search a train carrying troops.

The train chugged its way slowly through the day and night and it arrived at its destination, a goods depot just outside Paris, early in the morning. We left the train and were led by a back route out of the depot and taken to a railwaymans’ café for a coffee and rum. After that we took the Metro into Paris and at the same time lost sight of the French members of the party. On our arrival in the centre of Paris we were dumped in a café for an uncomfortably long time, trying to pass the time without talking but still trying to look alive – my two companions had not a word of French between them and my French was the sort that the French understood but which caused them to burst out laughing. It was a very unnerving few hours as my friends deemed that, as Englishmen, they had the right to talk their native language, whatever the situation, and could not understand that not all French may be sympathetic towards them.

However, after a few hours, and a lot of coffee, had passed our guide returned… He then took us on a sightseeing tour of Paris, by foot. My first view of the ‘Eternal Flame’ at the Arc de Triomphe was alongside two German soldiers on local leave – a most peculiar feeling. Towards evening we were taken for a meal of unrationed soup with some bread and then to a seedy hotel, where we were to spend the night.

The next afternoon they took the train for Bordeaux. They got off at Lillebourne, the last station before Bordeaux, and took a stopping train to Coutras then hid in undergrowth until morning. A German motorcycle patrol passed and the escape party made for the Vichy France outpost where they were welcomed with coffee and bread. They began walking to Mussidan but were delighted to be given a lift in a Red Cross ambulance to Perigeux. They then took a long train journey to Nimes.

At Nimes, Henri informed us that that was as far as he took us and the Gendarmes there would take us to a camp from which the British servicemen were being repatriated. After having collected our identity cards from us, for re-use he said, he removed our photos from them and presented them to us. His last words to us were to tell us where to find the Gendarmerie, he could not afford to be identified with us for the sake of the parties following.

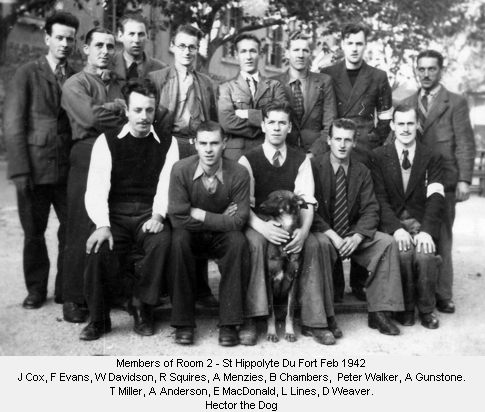

Being at the time rather naïve and being, as it were, stranded in an unknown French town we had no other option but to believe him and do as he said. The Gendarmes were very pleasant and treated us well and fell in with Henri’s story of a repatriation camp. They provided us with a supper of coffee, a chunk of bread and a piece of gruyere type cheese and a bed to sleep in, albeit in a locked cell. Early next morning we set off for Nimes railway station and took a local train and on the morning of 14th of February 1941, I arrived at the Detachement ‘W’, St Hippolyte-du-Fort, Gard. I found myself amidst two hundred or so survivors from Dunkirk, Calais, Boulogne and St Valery, survivors from almost everywhere in North and North-East France where the B.E.F. had operated.

For the first six weeks or so after we arrived at St Hippolyte we were allowed to leave the camp during the day so long as we were back for the evening roll-call… Our rations consisted of half an ounce of cheese with a small slice of bread and half a cup of coffee substitute in the morning and then nothing until the evening meal when we received the rest of the daily bread, making up a total of about 125 grams a day. The rest of the evening meal consisted of a meagre helping of vegetables consisting of, for example, spinach one day or overgrown bitter chicory another day… Friday was red letter day most times, as we were served up with a white fish paste which whilst not very filling in the portion we received, was at least very tasty. One Friday meal however was not so appetising. It consisted of three or four small raw salted sardines. Not fancying the idea of raw fish we took them back to the barrack room and tried to boil them. Much to our dismay the boiling water dissolved the flesh off the fish and all we were left with were the fish skeletons floating in the boiling water.

The American Consulate was responsible for ensuring the welfare of British internees and gave them a small monthly allowance, enough to buy a modest meal in the village. Peter remembers having little energy but he enjoyed exploring the village. In April 1941 the German Control Commission forced the French to confine internees to their camps except for organised escorted trips, this caused disappointment, but the arrival of Red Cross crates containing food, cigarettes and tobacco for the whole camp was appreciated.

In March, 1942, the camp was moved to a border fort in the French Alps called ‘Fort de la Revere’.

Three things happened soon after our arrival at the fort which helped to raise our spirits somewhat. Firstly we were allowed to purchase radio sets from a shop in Nice and every room clubbed up to buy a set. These could receive short wave stations and we were able to listen to the news from London… (next); the arrival from the Red Cross of British army clothing, enough to outfit every member of the camp with a complete uniform and two sets of shirts and underclothes… The other issue from the Red Cross was that of individual food parcels. Some were Canadian, the preferred type, and the others British but still very welcome. The Canadian parcels contained a pound each of spam and butter and a large tin of klim – milk powder – also jam, large cracker type biscuits, prunes and a large block of eating chocolate and coffee, together with a packet of sugar. The British parcels contained various tins; meat, or meat and vegetables, condensed milk, sugar, sometimes beefsteak puddings, margarine, tea, a small packet of biscuits and raisins. No doubt the passage of time has caused me to forget some of the contents; but I am eternally grateful for the efforts of the Red Cross and those at home who supported it.

After two RAF officers escaped from the fort, all remaining RAF officers were removed. This failed to prevent further attempts and 58 internees escaped and, in September 1942, the camp moved again. They were taken by train from Nice to the Camp de Chambaran, Isere, formerly a French Air Force training camp in the foothills of the Alps near Grenoble. It was more comfortable than the fort, but after the Allied invasion of North Africa they could not stay. The camp was in the Italian zone of France and the internees were told they would be escorted through France to Spain.

One night however a fleet of ambulances turned up outside the camp and we were on the move again, eight to an ambulance, with what hand luggage we could pack in the time allowed. We set off to Modane, a French railway station just on the Franco-Italian border. Here we got on the train that was to take us to sunny Italy… We went through Turin, Alessandria, to Modena and arrived at the little town of Carpi in the Po Valley. From there we marched to our next home for nine months. This was the Italian POW camp – Campo Concentranento di Prigioneri di Guerra No.73 – and we were in Settore Una, ie. Compound 1, Hut 23. This was the first time most of the ex-internees had been Prisoners of War and the introduction was not a kind one.

The camp was large – capable of holding about 6,000 prisoners – and quite new. Constructed for prisoners taken at Tobruk and El Adem in the summer of 1942, it held British, Australian and South African troops.

The food from the Italians was marginally better than what we had received in France and consisted of an artificial coffee drink with a small baguette type loaf of maize bread first thing in the morning, followed by about a pint of rather watery minestrone soup at midday and again in the evening the same soup. Red Cross parcels were only one between two men per week. As a result of the shortage of solid food the camp was busy at night with people tripping to the latrines.

In Hut 23 the main way of passing time was in conversation, reading when one was lucky enough to get hold of a book, and a pastime that was new to us ex-internees, cracking lice between two thumb nails.

Peter had a disagreement with the NCO in charge of the hut and was given seven days in prison. He was the only prisoner and got on well with the guards who shared extra rations of olive oil and onions with him. He enjoyed being part of the working party, keeping the camp tidy, and when he was released the Sergeant in charge offered him a place with the party. He received an extra loaf of bread for his work and soon noticed his fitness improving.

In the spring we played a very vigorous form of touch rugby. The soccer players in the camp thought that we were mad and, as we played all through the summer, so did the Italian guards. We enjoyed it though. The hut 23 ‘Wasps’ playing in army vests, dyed yellow with a stripe of black round the middle, became the Champions of Settore 1.

After the invasion of Sicily and the Allied assault on Italy, the prisoners expected a backlash from the Italians, though none came. After the Capitulation of Italy on the 8th of September 1943, the camp inmates received orders to stay and await liberation by Allied forces, but the day after the Italian guards had fled, the camp was surrounded by German armoured cars.

We were ordered to pack up what we could carry and were then marched to the nearest railway siding where awaiting engines stood… We were ordered into these – about 50 men to a truck with a loaf of bread and a bit of cheese per man. As soon as the train was loaded it set off on its journey to Germany.

Peter was taken to Stalag IV ‘F’ at Hartmannsdorf near Chemnitz. It was a huge camp with several thousand prisoners of different nationalities. The camp seemed unprepared for new arrivals and they were penned in a compound until the next day.

The next morning the Germans began processing us in groups of a hundred. We had our heads shaved… the next stage was delousing and bathing, where we stripped and our clothes went through a stoving machine to kill any lice, whilst we were painted with delousing ointment in all our private places and passed forward into the shower. Here we had a soapless shower and dried ourselves as best we could on the bits of cloth which the Germans provided. We were then reunited with our clothes and possessions, got dressed and the processing continued.

Having noted our army number the Germans then gave us our German Prisoner of War number. I now became No. 247892. It seems such a little thing but after the first few days as a POW had passed I think that this was one of the most depressing things to have happened. I no longer felt to be a British soldier but rather a German POW.

After having been given our numbers we were next finger-printed and photographed with our numbers in front of us. When the processing was complete we were admitted to the British prisoners’ compound and allotted a hut. After being at Stalag IV ‘F’, for about a week, a hundred or so of us were sent to a working camp situated in a small market town nearby called Mittweida, 20 km or so towards Dresden. This work camp went under the name of Arbeitskommando M88.

The work camp provided labour for a nearby electronics factory. Peter was first employed digging trenches for water pipes. He and John, a fellow POW, then started work at a joiners’ shop in Mittweida. They helped the machine operators, stacked timber and took finished furniture and coffins to customers. Most of the German workers were Nazi supporters, though not all were party members, and appeared to despise Poles and Slavs.

The way in which (Polish) slave workers and Russian POWs were marched about their business in the midst of winter, inadequately clothed in rags and wearing wooden clogs with their feet just wrapped up in old cloth, without any show of concern on the part of the civilians made it very hard for us to feel any sympathy at all for their (Germans) sufferings under the air raids. When, after the invasion of France, they began boasting about how the V1 and V2s had destroyed London any sympathy that we had left went. Although perhaps we shouldn’t have done we derived a great deal of satisfaction from their confusion with the air raid warnings towards the end of the war.

Most days were spent helping the machine operators or stacking the newly delivered planks of wood. The two people we worked with most were Walter, a thirty or so year old, lapsed communist and Wolfgang, a seventeen year old member of the Hitler Youth and panzerfaust operator in the local volkssturm. As a communist, Walter had served a sentence, pre-war, in a concentration camp and was well aware of what happened there. Wolfgang lost his enthusiasm for his Panzerfaust after the bombing of Dresden and the advance of the Allies towards Saxony.

Soon after their arrival, Red Cross parcels began to arrive weekly and morale in the camp improved. The inmates talked about their wartime experiences and their plans for the future and in the Spring of 1944, some brass musical instruments arrived and a small band was established. The evening concerts became very popular.

These concerts soon caught the attention of the German civilians taking their evening strolls and their numbers soon attracted the attention of the German authorities. The guards were ordered to make us put blankets up on the barbed wire, the sight of British POWs enjoying themselves was not good for the German morale, or so they thought. D-Day gave a big boost to our morale which had already started rising with the turn of the tide and the increasing severity of the bombing of German cities, even the Polish slaves looked happier in their misery.

As the early months of 1945 passed, the daylight sky on many days was filled with the lace like tracery of the condensation trails of American planes on their daylight raids. This was a beautiful sight, both visually and from the point of view of morale, tinged with a great sadness when one of these spearheads burst into silver fire and started twisting downwards to earth like a falling leaf. Sometimes little toy-like parachutes could be seen floating down in the distance but other times there was just a flash and then nothing.

With the increased air-raids the prisoners were made to dig trenches. On one occasion a bomb was dropped about half a mile from the camp, after a raid on Dresden, but no-one was harmed. By the end of February the bombing of transport facilities affected the delivery of mail and parcels. On the 21st of April, the Americans arrived.

There were scenes of wild rejoicing as an American tank and two jeeps came driving up the valley to the camp gates, and the odd tear as their crews were greeted, – five years had been a long time. Our two guards had now disappeared into the countryside with our blessing, as they had not been so bad on the whole.

The Americans provided K rations and gave orders for them to remain and keep order between the foreign and slave workers.

On the 25th of of April the Americans told us to commandeer what transport we could and then make our way to Gera, where we could be picked up by army trucks and taken to Erfurt to be flown from there as soon as an aircraft was available. The next morning the convoy set off, several vehicles crammed with very happy British soldiers. Reaching Gera by early evening after a very pleasant drive in warm, spring weather we were billeted in private houses for the night. What a luxury it was to sleep in a proper bed after all these years – even if it was a rather peculiar German bed.

The next morning we climbed up into big, three-ton, American trucks driven by the Transport Corps, who drove long hours on what was known as the ‘Red Ball highway’, a route reaching back to the stores depots in France. On this highway they had complete right of way but were now becoming extremely tired. We were bowling along quite nicely towards Erfurt when, all of a sudden, the truck started to lean to the right and after a few moments the lean became more and more pronounced until eventually the truck came to a halt, remarkably gently, on its side with everybody inside all of a jumble. The driver had dropped asleep at the wheel but fortunately the roadside ditch was wide but not very deep and our descent was very gradual. The driver was woken by the accident and we soon managed to get the truck back on the road and resumed our journey.

They arrived at Erfurt in the late afternoon of the 26th of April and a nominal roll was taken. The next morning they were flown to Brussels and then to England.

We were delivered by truck to a very large house near High Wycombe. Here we were processed with great efficiency and kindness. First we were dusted under our clothes with DDT, then given a very good meal. Then we were given a bath and a complete set of uniforms with underclothes and a kitbag and all our details were taken. A telegram was sent for us to our folks at home. That evening the repatriation centre put on a dance for the ex-prisoners.

The next morning they were given leave papers for two months and an advance of pay. Then Peter made his way back to Halifax.

This is a record of Peter Walker’s Service in the Duke of Wellington’s Regiment, From May 1939 to April 1945.

Interviewed by Tracy Craggs, Regimental Archives Section, Audio Archivist.

© Photo’s by Peter Walker