Quatre Bras and Waterloo, 1815

Quatre Bras, 16th June 1815

In April, 1814, Napoleon Bonaparte abdicated and it seemed that the wars which had raged since the French Revolution of 1789 had come to an end. But Napoleon escaped from exile and, in March 1815, made a triumphant entry into Paris, forcing the Allies to invade France again. The Duke of Wellington was to attack from Belgium, supported by the Prussians under Field Marshal Blucher. Russian and Austrian armies would invade from across the Rhine.

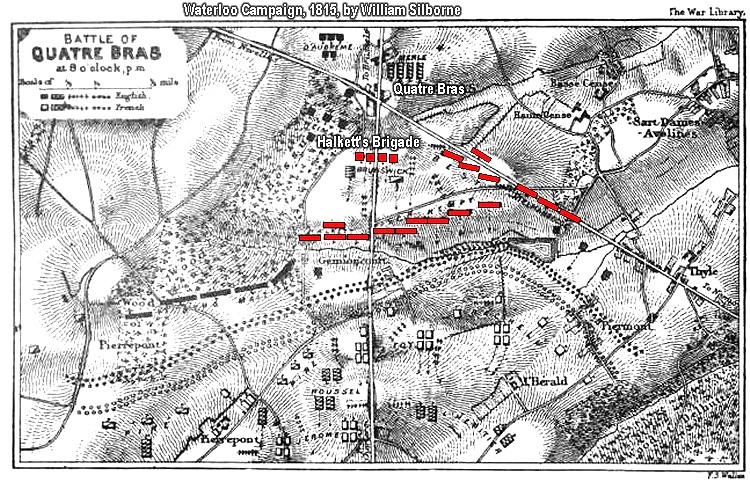

Napoleon decided to deal with his enemies piecemeal. On 15th June he marched into Belgium with 140,000 men of the Armee Du Nord, catching Wellington and Blucher off guard as Marshall Ney, one of Napoleon’s most dashing cavalry generals, neared the vital cross roads at the small village of Quatre Bras. The 33rd, part of Sir Colin Halkett’s 5th Brigade (3rd Anglo-Hanoverian Division), marched 20 miles to relieve its defenders. At 5.30 p.m. the 33rd engaged French infantry who were trying to turn their flank. Lieutenant William Thain, the Regimental Adjutant, described how:

“We gave them a most beautiful volley and charged, but they ran faster than our troops (already fatigued) could do, and we consequently did not touch them with the bayonet.”

But there was a greater threat. French Cuirassiers, armoured troopers on heavy horses, charged the Brigade from close range. Such men could ride through infantry in line, forcing them to adopt a defensive square for protection. Surprised by the onrush, the 33rds supporting Regiment the 69th was caught in line and cut down as the 33rd successfully formed square to repel the attack.

After reforming into line to continue the advance, the 33rd were again charged by cavalry, this time closely supported by artillery. Squares were vulnerable to artillery fire, as the 33rd were to discover. Private George Hemingway wrote home afterwards telling how their attempt to form square failed:

“The enemy got a fair view of our Regiment at that time and they sent cannon shot as thick as hailstones…we seen a large column of French cavalry called Cuirassiers advancing close upon us. We immediately tried to form square but all in vain as the cannon-shot from the enemy broke down our square faster than we could, it killed nine or ten men every shot, the balls bursting down amongst us and shells bursting in a hundred pieces…”

The first regimental officer killed, Captain John Haigh, fell bravely trying to steady the front face of the square in the teeth of this devastating fire. His brother, Lieutenant Thomas Haigh, saw him die and was himself later mortally wounded at Waterloo.

Having seen the fate of the 69th when caught in the open, the 33rd fell back to the cover of the trees in the nearby Bois de Bossu. Here they reformed, but were held in reserve until nightfall brought the fighting to an end. Ney had been held, gaining valuable time for the Allies.

The 33rd went into action 561 strong. Its casualties were:

Killed – 3 Officers and 13 men.

Wounded – 7 Officers and 64 men.

Missing – Regimental Sergeant Major Colbeck (POW) and 8 men.

The 3rd Battalion, 14th Foot (4th Brigade, 4th Anglo-Hanoverian Division), having received orders to march to Enghien and, from thence, to Braine le Comte, was making its way to Waterloo and could hear the firing from Quatre Bras. Early on 17th June the Battalion left Braine for Nivelles and, marching in pouring rain, that evening the 4th Brigade ended up as part of the 2nd Division, on the extreme right flank of the Allied line, blocking the Nivelles road, the remainder of the 5th Division being ordered to the rear of the position.

Waterloo, 18th June 1815

On 17th June, Wellington withdrew to his chosen defensive position covering the approach to Brussels, the ridge of Mont St. Jean near the village of Waterloo. The high ground allowed his favourite tactic, use of the reverse slope to conceal his troops from the enemy – Wellington described a general’s greatest skill as the ability to guess “what was on the other side of the hill”. The aim was to hold Napoleon until the arrival of the Prussian army, when he would be outnumbered.

By the time the 33rd had covered the 10 miles to Mont St Jean, without rations or greatcoats, during a violent thunderstorm, they were soaked to the skin. Exhausted, they tried to sleep on the muddy ground. At 9.00 a.m. they were in position with Halkett’s Brigade, on the right centre of the battlefield, behind the unpaved road connecting Hougoumont Chateau and the farm of La Haye Sainte. These had been fortified as defensive outposts. The rain delayed Napoleon’s attack, the mud making it difficult to bring up his artillery, but about 11.15 a.m. the French opening barrage began.

The 33rd stood their ground, protected by the reverse slope, as the French pressed home their assault on Hougoumont, which continued to hold. An attack on the centre was beaten back by Picton’s Division and the British cavalry. Realising that he needed to take La Haye Sainte, Napoleon ordered another bombardment at 3.30 p.m. Soon afterwards Marshal Ney and his cavalry moved forward, forcing the British infantry into squares, Lieutenant Frederick Hope-Pattison of the 33rd wrote:

“…our Brigade was placed in the most trying position in which a soldier can find himself. Held in reserve except in resisting repeated charges from the French cavalry, which we inevitably repulsed, we were yet exposed to the destructive fire of artillery which occasioned many casualties”.

Wellington himself rode up to Halkett to see how it stood with his Brigade. The situation was desperate and casualties were mounting. Halkett asked the Duke for a breathing space for his men, “My Lord, we are dreadfully cut up; can you not relieve us for a little while?” “Impossible!” “Very well my Lord, we’ll stand until the last man falls”.

By 6.30 p.m. the 33rd had withstood four charges and the French Cavalry had been destroyed. La Haye Sainte had fallen and the 33rd and 69th were now so weak they formed together as a single under-strength battalion. Wellington looked at his watch and was heard to say, “I wish it was night or the Prussians would come”.

At 7.00 p.m. Napoleon ordered his veteran Imperial Guard forward. As the leading column closed in, Halkett took the 33rds Colour from the dying hands of Lieutenant John Cameron and led his Brigade into action. Halkett fell wounded, his command taken by Lieutenant Colonel William Elphinstone of the 33rd, but as the French drew closer Wellington brought his Guards Brigade into action. Hidden behind the ridge, their sudden appearance followed by a devastating volley made the enemy recoil, before breaking, as the Guards charged home. At the same time, the other advancing French columns were halted by fire from the flank and panicked by the arrival of the first Prussian troops on their right. Seizing the moment, Wellington gave the order for a general advance. By 9.00 p.m. Wellington and Blucher had met, the French army had collapsed and Napoleon was in flight.

After advancing against the French Chasseurs (Light Infantry), the 33rd and 69th halted at Hougoumont, where they prepared to bury their fallen comrades. As the casualty returns – the ‘butcher’s bill’ – were brought to him, Wellington was overcome with emotion. He later wrote, “Next to a battle lost, the greatest misery is a battle gained”

The 33rd lost:

Killed – 4 Officers and 32 men.

Wounded – 8 Officers and 92 men.

Missing – 48 men.

The Battle Honour ‘Waterloo’ was awarded to the Regiment and a medal struck for those present at the battle. Lt Col Elphinstone returned 68 medals issued to men of the 33rd who had not been with the Regiment, for various reasons, on the 18th June.

The Battle Honour ‘Waterloo’ was awarded to the Regiment and a medal struck for those present at the battle. Lt Col Elphinstone returned 68 medals issued to men of the 33rd who had not been with the Regiment, for various reasons, on the 18th June.

The 2nd Battalion 14th Foot watched Jerome Buonaparte signal the start of the cannonade at Hougoumont which was to last for six hours. At about 3.00 p.m. in the afternoon a renewed attack on Hougoumont necessitated the movement of troops to its support and the 14th received orders to advance and form square and, after taking a number of casualties, to lie down and then to seek shelter further forward in a less exposed position. Towards evening a large body of French cavalry attacked and, while they were wheeling amongst the British and Brunswickers’ squares, the Allied troops got a welcome respite from the artillery fire. The French cavalry, being unable to break into the squares, was eventually repelled in some disorder. The Regiment bivouacked that night near Hougoumont.

The 2nd Battalion was 620 strong (Rank and File – from the monthly return) and lost one Officer and 28 men killed and wounded during the battle.

The Waterloo medal was issued to all in the three Brigades of the 5th Division, as the 6th British and 6th Hanoverian Brigades were present, but the units of these Brigades did not have the distinction of inscribing ‘Waterloo’ on their Colours.